The Incarcerated ‘Worker’

By Giselle Garcia ’23, Legal Fellow for the Aoki Center for Critical Race and Nation Studies

The movement to abolish slavery remains alive 158 years after the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. Two thirds of incarcerated people in the United States are forced to work and do so under complete subjugation to the state. California is one of 16 states to sanction involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime. In February of this year, ACA 8 was proposed on the Assembly Floor to amend Article I, Section 6 of the California Constitution to prohibit slavery and involuntary servitude without exception, as follows:

- Slavery in any form is prohibited.

- As used in this section, slavery includes forced labor compelled by the use or threat of physical or legal coercion.

The proposal has passed in the Assembly and is currently being analyzed by the Senate. However, this is second time this amendment has been proposed after failing in 2022. The bill met its demise last year after the California Department of Finance opposed the proposal estimating a $1.5 billion yearly cost to pay incarcerated workers a minimum wage. Opposition to the amendment based on financial considerations should raise red flags about the extent to which forced labor is necessary to sustain prisons.

The ACLU and the University of Chicago Law School Global Human Rights Clinic published a comprehensive research report containing data providing insight into how much incarcerated worker labor is relied on by correctional institutions across the country to maintain themselves operational and profitable. The report highlights that the overwhelming majority of the approximately 800,000 incarcerated workers offset over $9 billion in operating costs.

Wage theft and poor working conditions are other ways correctional departments offset expenses and generate profit. Being forced to work under dangerous, industrial, conditions without safety gear or minimal training on how to operate heavy machinery often leads to life changing injuries such as second and third-degree burns, lacerations, amputations, toxic chemical exposures, and death. When such injuries occur, facilities often fail to provide adequate medical treatment and, in some instances, have even simply given individuals over-the-counter topical cream to treat second- and third-degree burns. Incarcerated workers are forced to endure these risks for cents on the dollar.

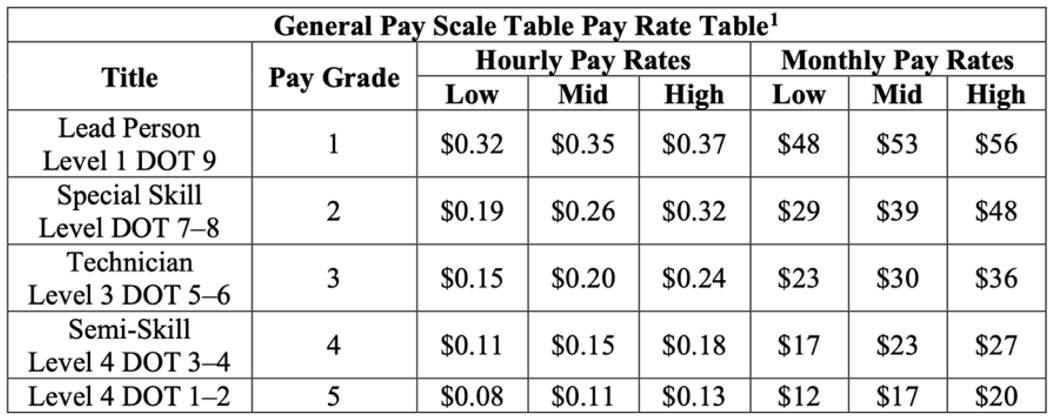

Many states such as Florida are not required to pay incarcerated workers any wages for their labor, and facilities that do pay meager wages. The California Secretary of CDCR has established the following general pay rate scale for incarcerated workers.

Audra Dawson, a mother, grandmother, and an incarcerated worker at CDCR California Correctional Women’s Facility shares, “As a working-class inmate, my body breaks down from years working for the prison and there's no retirement plan for me, no unemployment. A human being deserves to earn a decent wage for a hard day’s work—in or out of prison. If I can be trusted to labor for CDCR and provide the same quality labor as any paid staff, I should also receive decent pay.”

Many argue that the prison labor model is not exploitative since incarcerated persons gain useful experience that aids their rehabilitation. Yet, the extent of degradation undergone by incarcerated workers is profoundly detrimental to rehabilitation and in violation of basic human rights.

The South’s Penal Plantations serve as an example of the perverse nature behind the prison labor model. Every incarcerated person in Angola Prison, 75 percent of whom are Black, is forced to work in fields cultivating cotton and other crops. These same fields were original slave plantations which still have limited access to water, no restroom facilities, and are under the supervision of armed correctional officers on horseback. Abstaining from work—no matter how egregious—is not an option in prisons. Individuals report being punished for being unwilling or unable to work. Absences or poor performance due to illness are considered rule violations and lead to placement in solitary confinement for arbitrary amounts of time, penalties extending served time, or denied benefits like family visitation. In these ways, coercion operates through punishment and deprivation if an individual refuses or is unable to work. Individuals instead could be participating in rehabilitative programs.

Despite many legal challenges to such conditions, incarcerated workers have been stripped from rights including the ability to unionize, the right to minimum wage, and workplace protections—this includes immigrants in detention facilities. Though a state constitutional amendment will not immediately remedy these injustices, it will provide a foundation future litigation and propel further legislative reform to establish protections for incarcerated workers—this is why ACA 8 is a crucial first step.

We must recognize that calling incarcerated individuals ‘workers’ displaces the perverse nature of their true conditions, that ultimately, they are state-managed slaves. However, improving labor conditions in the short-term for incarcerated persons coerced to work can eventually serve to render prisons economically unsustainable and allow the current corrupt carceral system to implode—forcing us to think of solutions to deviance beyond the current model. Though solutions for addressing the carceral state may vary across the political spectrum, the abolition of slavery in all forms should be a nonpartisan issue for everyone to support. And it begins with calling the current incarcerated labor model what it is, slavery.